Vikram Sampath's book on Tipu Sultan: A journey of tyranny and legacy

Vikram Sampath's book delves into Tipu Sultan's reign, marked by zealotry and strategic tolerance. It challenges narratives, focusing on the ruler's kingdom preservation efforts.

- Jan 03, 2025,

- Updated Jan 03, 2025, 6:12 PM IST

Vikram Sampath’s magnum opus on Tipu Sultan explores the tumultuous period of Mysore’s history from 1760 to 1799, a time dominated by the reign of Haider Ali and his son Tipu Sultan.

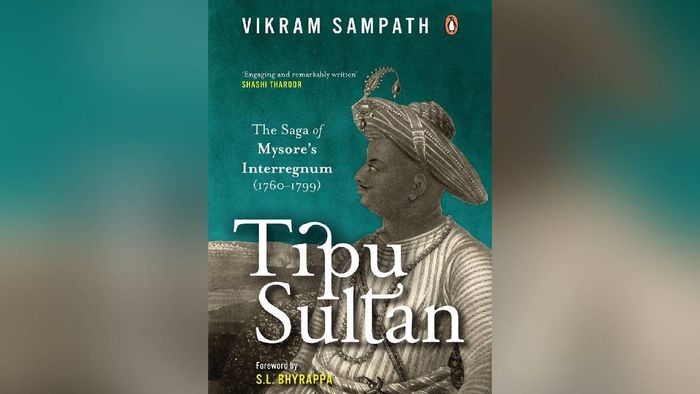

The book 'Tipu Sultan: The Saga of Mysore's Interregnum (1760-1799)', possibly one of the most extensive works written on Tipu Sultan, is a painstakingly researched account that combines narrative brilliance with academic rigor. Through its exhaustive notes, bibliography, and index, Sampath’s book presents a comprehensive examination of the father-son duo’s rule, revealing their contrasting personalities, administrative policies, and military exploits.

The author’s analysis of Tipu Sultan’s legacy, particularly in the context of religious intolerance, warfare and his controversial portrayal as a freedom fighter, is a profound critique of Indian historiography.

The book depicts how the naming of a Pakistani naval vessel after Tipu Sultan during the 1965 India-Pakistan war highlights the contrasting views of his legacy. While some see him as a progressive ruler and freedom fighter, others regard him as a religious zealot and tyrant.

The narrative begins with Haider Ali's rise to power as the de facto ruler of Mysore, despite the presence of the titular Wodeyar king. While Haider Ali’s treatment of both allies and rivals was often marked by treachery and vindictiveness, he nonetheless displayed a degree of religious tolerance towards his Hindu subjects.

In his book, Sampath recounts the atrocities committed during Haider’s Malabar invasions, including bounties on Nair's heads and the capture of women for sexual slavery - revealing a man driven by power and greed, willing to exploit violence to achieve his ends.

In contrast, Tipu Sultan’s reign was marked by overt religiosity and bigotry that shaped his administrative and military policies. Tipu’s strict Islamic education, instilled by his father, foreshadowed the zealotry that would define his rule. The book explains how his actions, such as the massacre of the Mandyam Iyengars during Deepavali and the gruesome atrocities in Malabar, including the hanging of mothers and children, stand as testament to the inhumanity of his rule. Sampath’s inclusion of these chilling details paints a vivid picture of a ruler whose religious fervour often overshadowed pragmatic governance.

Tipu’s claims of being a freedom fighter are rigorously scrutinised. The notion that he fought against the British for India’s liberation is dismissed as a myth. Sampath argues that Tipu’s primary concern was safeguarding his kingdom and wealth, rather than any overarching vision of Indian independence. Tipu’s repeated betrayals of allies, such as the execution of his envoys upon their return from a failed mission to France, further illustrate his opportunism.

The book’s detailed accounts of Mysore’s wars provide a critical perspective on Tipu’s military strategies and their impact on Indian history. The First Anglo-Mysore War shattered the myth of European invincibility, while the Third and Fourth Wars exposed Tipu’s strategic blunders and overreliance on foreign alliances. The final siege of Seringapatam, culminating in Tipu’s death, marked the end of an era and underscored his inability to adapt to changing political realities.

Sampath’s comparison of Tipu’s downfall to Saddam Hussein’s defeat in the Gulf War is particularly striking, highlighting the parallels in their isolation and ultimate demise.

Sampath does not shy away from examining instances where Tipu displayed tolerance, such as his patronage of the Ranganathaswamy Temple and Sringeri Math. However, these acts are contextualised as pragmatic gestures aimed at consolidating support among his Hindu subjects following his military defeats.

The selective nature of these actions, juxtaposed with his systemic discrimination and atrocities, reinforces the author’s conclusion that Tipu’s rule was far from the secular ideal often portrayed by revisionist historians.

The book also addresses the historiographical distortions that have shaped Tipu’s image. Sampath critiques the romanticized accounts of Left-leaning historians who downplay or ignore the sultan’s bigotry and violence. The revenue code’s provisions, which incentivized conversions to Islam through tax exemptions, further debunk the myth of his egalitarianism.

Sampath’s book is adorned with rare paintings and illustrations that enrich the narrative, providing a visual dimension to the historical events and personalities discussed. The foreword by S. L. Bhyrappa, a renowned Kannada author and historian, sets the stage for the book’s uncompromising approach to historical truth.

While the book’s focus on battles and military campaigns might seem excessive to some readers, it is a necessary reflection of Tipu’s political and military priorities. The author’s ability to balance scholarly analysis with engaging storytelling makes this a compelling read for both academics and general readers.

Vikram Sampath’s biography of Tipu Sultan is a monumental achievement that challenges prevailing narratives and offers a nuanced perspective on one of India’s most polarizing historical figures.