From Famine and Friendship to Revenge and Rebel: A novel revisits Mizoram's darkest era

“To the great Mizo people, may your suffering, your sacrifices, and your stories, never be forgotten," says Nikhil Alva dedicating his first novel to the Mizo people.

- Mar 01, 2024,

- Updated Mar 01, 2024, 8:52 AM IST

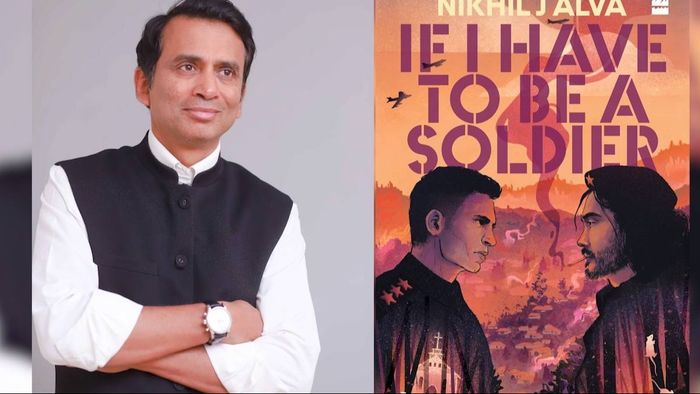

One balmy winter afternoon in Jaipur, when the sun was out and beginning to cast its warmth, I saw people rushing to fill an empty open hall. I followed them and found myself a seat somewhere behind. Soon, the open hall was brimming with anticipation. On stage was Nikhil J. Alva in conversation with Koël Purie Rinchet at the recently concluded Jaipur Literary Festival. In between a very engaging conversation, he recited select passages from his latest book ‘If I have to be a soldier.” Alva, with his soft-spoken demeanour, clarified that his writing didn't aim to emulate an insider's perspective but rather that of an astute observer. He clearly asserted that he was not an “expert,” yet the very existence of his book spoke volumes about his profound passion and concern for a nearly forgotten facet of India. This neglected region, steeped in a history marked by bloodshed and anguish, became the canvas for Alva's narrative.

His debut novel, If I have to be a soldier is set against the backdrop of the Mizo Hills in India's Northeast during the mid-1960s, intricately intertwining with the historical genesis of the MNF insurgency. The roots of this insurgency can be traced back to 1959, when the Mizo Hills faced the severe famine known as ‘Mautam’, a tragic event that marked the flowering of bamboos. In 1959, the Mizo Hills experienced a devastating famine known as the “Mautam Famine.” The crisis stemmed from the widespread flowering of bamboo, leading to an exponential increase in the rat population. As the rats depleted bamboo seeds, they turned to crops, infiltrating homes and villages, wreaking havoc. The aftermath was grim, with minimal grain harvested, pushing many Mizos to forage for sustenance in jungles, while others sought refuge in distant places. Unfortunately, a significant number succumbed to starvation.

Alva, an award-winning producer, director and writer draws his inspiration from his childhood experiences accompanying his mother, Margaret Alva, a prominent political leader of the Indian National Congress. Nikhil weaves a riveting story that reflects the tumultuous times and the profound impact it had on the people of Mizoram. The novel introduces readers to Captain Samuel Rego, an Indian Army officer and the son of a Baptist preacher, as he confronts his past and a bitter childhood friend-turned-foe, Sena Aliott. The story unfolds with interrogations, moral dilemmas, and choices that propel the characters into a captivating tale of revenge, rebellion, identity, and love against the brutal war for Mizo independence.

If I Have To Be A Soldier, published by Harper Collins, transcends the boundaries of a mere historical thriller; it becomes an important journey through time, exploring forgotten lands and the cultures of the people of Mizoram. Nikhil's narrative prowess, coupled with his firsthand insights into the region's history, adds depth to the novel, offering readers an immersive experience. This debut work not only hints that Alva is a master storyteller but indeed a perceptive and a careful observer of the intricate human complexities and the socio-political landscape of the Northeast, a region often marked by fragmentation.

In an interview with Hoihnu Hauzel, Alva discusses the reasons behind writing the book and emphasizes the significance of Mizoram's history.

Growing up in New Delhi, you had firsthand experiences with politicians and leaders from Northeast India, including former guerrillas with fascinating stories. How have these memories, emotions, and experiences influenced the characters in your novel, and what role do they play in shaping the narrative?

At the core of every ‘fictional’ character created by a novelist, is a real person! Obviously, there are many fictional elements that get layered onto this core and the character that emerges is an amalgamation of the real and the fictional. While growing up in Delhi I was lucky to meet many intriguing characters from the Northeast – both because of my mother’s political work and connections with the Northeast as well as my own experiences as a student and later as a media professional. Some of these characters have seeped into the novel and helped enrich it and bring it to life.

Can you elaborate on the inspiration behind setting your novel If I Have to Be a Soldier against the backdrop of the Mizo National Front's armed rebellion in 1966, exploring themes of identity, survival, betrayal, and love?

In my childhood I made numerous visits to the Northeast, accompanying my mother, Margaret Alva, who was the Congress party’s point person for the region for many years, beginning in the mid-seventies. In those days the insurgency in Mizoram and in Nagaland were at a peak and security was tight. I recall you couldn’t travel on the roads at night because there was a real risk of being attacked by insurgents and there was an air of fear and insecurity wherever you went. I found it intriguing that my mother was often introduced locally as someone who had come to visit ‘all the way from India’ and even as a boy, I sensed a strong feeling of alienation and disillusionment with the policies of New Delhi amongst the local population. My interest in the Northeast originates from those early experiences. Later, when I heard about the Mautam in the Mizo Hills and the incredible casualty between the once-in-48-year flowering of the bamboo, the rat plague that followed, which in turn lead to a terrible famine, the mishandling of which by the government triggered the brutal 20-year long insurgency, in which thousands died, I was intrigued enough to begin researching the subject. The more I read, the clearer it became to me that this was an incredibly powerful story that I had to tell. The story had many layers and after much thought I decided that the best way to tell it was in the form of a novel with fictional characters set against real- historical-events that shaped the Mizo insurgency.

What aspects of Northeast pain you the most, and do you believe it remains misunderstood despite the passing years?

I believe after independence the leadership in Delhi was preoccupied with a host of major problems that they had to deal with – the pain of partition, famine and food shortages, creating a constitution, our first elections, building essential infrastructure, the wars with Pakistan and China and so much more. It was a very difficult time. Perhaps, as a result of that preoccupation. The Northeast and its problems, unfortunately, didn’t receive the attention they rightfully deserved, leading to growing disillusionment amongst local communities in the region – who felt their voice wasn’t being heard and that they were being taken for granted. It didn’t help that most of the Northeast was clubbed under a giant Assam State, with little regard for local sentiment, culture, language and religious beliefs. At the root of the insurgencies in the Northeast has been a lack of dialogue between New Delhi and communities that felt increasingly exploited and marginalised. And a fundamental disrespect for points of views at odds with the larger Indian nationalistic sentiment. Coming on the heels of India’s disastrous war with China in 1962 and the stalemate with Pakistan in 1965, the Government of India chose to deal with the Mizo insurgents in 1966 with an iron hand instead of trying to resolve differences through dialogue and negotiation. I believe that was a mistake. The state of Mizoram that was created in 1986, through the Mizo Accord, could possibly have been conceded much earlier, bringing the insurgency to an early end, saving thousands of lives.

Even more recently, the terrible ethnic violence in Manipur and loss of lives, could have been avoided by strong armed intervention by the centre – perhaps even the imposition of President’s rule. While the people of the Northeast have undoubtedly felt a sense of alienation from India, I believe with the youth of the Northeast travelling to different parts of India in large numbers for education and for jobs, there is a growing interconnectedness between the Northeast and the rest of India, resulting in a reduction in the feeling of alienation.

Share your takeaways from each chapter, such as "I am a Soldier" and "Sammy’s War," including insights from chapters like "The Wailing of the Bamboo" and "Every Man Has to Die."

My novel begins with ‘Revelations’ and ends with ‘Lamentations’, which are the names of books in the Bible. The main body of the novel is further divided into a collection of 4-interconnected books: ‘I Am A Solider’. ‘Sammy’s War’, ‘The Wailing of the Bamboo’, ‘Every Man Has To Die’. In ‘Revelations’, I use the ‘wailing of The Witch’ as a metaphor for the terrible destruction that is to come to the Mizo Hills, when the bamboo flowers (which it does once every 48 years). In ‘I Am A Soldier’, I set up the basic ideological conflict that drives the book, using the device of the interrogation of a Mizo insurgent by an Indian Army officer. I also establish the critical relationship between my protagonist, Sammy, (the Indian army officer) and Sena, his childhood friend (the MNF insurgent) and the circumstances that cause the two of them to become fugitives.

‘Sammy’s War’ is about Sammy and Sena’s childhood in the idyllic village of Asakhua. At its heart is the discrimination Sammy faces. As an orphan with mixed parentage, he’s constantly bullied and humiliated by the other children in the village. Sena and Sena’s sister, Martha, are his only friends and the book sets up how those relationships develop and the incident that drives a terrible wedge between them, causing Sammy to flee Asakhua. In ‘The Wailing of the Bamboo’ the mautam and its terrible consequences are what drive the story. In this book Sena’s journey from village boy to feared MNF commander is covered as well as the early days of the Mizo Insurgency, the violence and the iron handed response of the Indian armed forces. ‘Every Man Has to Die’ is the final book in the novel, which is built around Sammy and Sena’s battle for survival and redemption – on the run together in the Mizo Highlands, hunted down by both the Indian armed forces and the MNF. In it, the two friends come to terms with their fractured past.

Finally, in ‘Lamentations’, the resolution of the Mizo insurgency and the dawn of peace and a new era in the Mizo Hills. Sammy’s love story too finds a bitter-sweet ending.

Your book touches on Zawlbuk, a bachelor’s dormitory that's no longer prevalent. In the process of writing, do you feel you are documenting a significant sociological shift in Mizos?

I have tried in my novel to weave in elements of traditional Mizo culture and society to paint the story with a strong Mizo flavour. I believe that Mizo culture is rich and diverse and has much to offer the world. In my novel I touch upon the Zawlbuk (bachelor’s dormitory) which was once an essential part of Mizo village life. In my novel I explain that this is no longer the case and the Zawlbuk (where they still stand in some villages) have been converted into grain stores and guest houses.

The Mautam left a profound impact on the Mizos. Do you believe they learned resilience from such a challenging incident?

Absolutely! I think the Mautam and the casualty between the flowering of the bamboo, the rat plague, the devastating famine that followed in which thousands starved to death, eventually leading to the 20-year long insurgency, is strongly etched into the memory of every Mizo. The violence in the Mizo Hills that began in the 60’s and went only till the peace accord was signed in 1986 consumed an entire generation of Mizos and has certainly made them more resilient and a stronger people.

In "Lamentation," you delve into the surrender of MNF and the dawn of peace, highlighting the relocation of 87 percent of the Mizo population to internment camps. As an Indian, how do you perceive these measures? Do you consider it a fair deal in some sense?

I think the forced relocation of over 80 per cent of the Mizo population into so-called ‘progressive villages’ which in reality were nothing but internment camps set up along the highways where the Mizo population were held at gun-point, and the burning down of hundreds of traditional Mizo villages, is one of the darkest chapters in modern Indian history. Along with it, is the bombing of Aizawl by the Indian Air Force, in which many innocent civilians were killed. As a human being I feel ashamed and saddened by what happened.

Your novel draws on the dark truths of one of India’s most secretive wars in Mizoram. How do you navigate the historical and contemporary significance of Mizoram's history, and why do you believe it has become a focal point of parliamentary discussions?

I would like to reiterate that ‘If I Have To Be A Soldier’ is a work of fiction, set against the historical backdrop of the Mizo insurgency. It’s not a non-fiction book or a thesis on the Mizo insurgency. To the extent that historical events serve as the backdrop against which my fictional characters are played-off and are critical to my plot, I’ve been true to the actual events that transpired – such as the Mautam, the formation of the MNF, Operation Jericho, the bombing of Aizawl, the forced relocation and burning down of Mizo villages, the peace accord of 1986 etc. My novel isn’t a political statement. My characters aren’t ‘black’ or ‘white’. Each is driven by their own motivation and to protect their own self-interests. They are each flawed in some way or the other – but they do have redeeming qualities too. It’s what makes them human and endearing. As for parliamentary debates – politicians often use and twist history for their own narrow political gains. As a novelist, that is of no interest to me.