IIT Mandi Faculty's new book sheds light on ethnopolitics in the Himalayan region

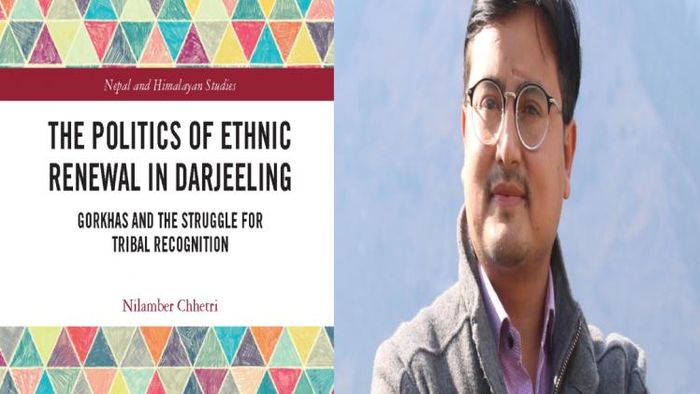

India Institute of Technology Mandi Faculty Dr. Nilamber Chhetri released a book on ‘Politics of ethnic renewal’ in the Himalayan region on March 27, published by Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

- Mar 27, 2023,

- Updated Mar 27, 2023, 6:08 PM IST

India Institute of Technology Mandi Faculty Dr. Nilamber Chhetri released a book on ‘Politics of ethnic renewal’ in the Himalayan region on March 27, published by Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

The book is based on the ethnopolitics of Darjeeling that has evolved in recent years.

The book revolves around the demands of the scheduled tribes for recognition which is also the longest quest to asset belongingness, rights and autonomy, nationwide. It also takes into account the varied forms of ethnic practices and while unraveling the complex discourse of ethnic mobilization in hills. It, thereby, links to the wider politics of classification and categorization in contemporary India.

The book features the demands of a separate state, to the current struggles for recognition as scheduled tribes. It also provides an in-depth understating of the ethno-politics of Darjeeling.

“The book is timely as it considers the discursive strategies adopted by ethnic associations to frame their identities as primitive and indigenous groups inhabiting the hills. While doing so the book captures the practices through which ethnic group re-cast their identities and retrace their genealogy in the ritual context”, said Dr Nilamber Chhetri.

The book provides examples of the nature of these demands as well as the methods in which people deal with exclusive and collective identity claims in their daily lives. The book explains how understanding the ethnopolitics taking place in Darjeeling can be used broadly to comprehend efforts for similar recognition taking place in South Asia.

It makes the argument that the more general politics of classification and categorization in modern India are what drive the latest mobilisations for ST status and urges for a reevaluation of the criteria for recognition.

In this context, the book starts a topical conversation about the politics of difference, alterity, and acknowledgment taking place in South Asia. It also reflects on how the state and the groups negotiate the tribe category in the midst of these concerns.

The book is intended for academics, students, and research scholars interested in the politics of categorization and state classification. Particularly, the book would be of interest to academics that used a multi-disciplinary approach to comprehend South Asian reality.

The active debate on India's classificatory practices and discourse around cultural rights and affirmative action can also be very beneficial for policymakers, activists, and law students.

For post-colonial researchers, students with an interest in the Himalayan region, and scholars generally interested in South Asian social and political reality, the book would be of enormous interest.

The book offers fresh perspectives on how to reconsider India's classification practices and the category of scheduled tribes by providing empirical illustrations laced with theoretical discussion.